Arthur S. Brisbane, the public editor of The New York Times, turned his attention this week to the newsroom's use of Twitter. He quoted from an e-mail interview with me, which I am posting in full here, with a few tweaks and links. The Public Editor: I’m working on a column about how Times staffers use Twitter: the journalistic benefits, the marketing benefits and any other benefits – as well as the costs, whatever they might be. I am, I confess, a newcomer to using Twitter and wonder whether it is a boon or a waste of time.

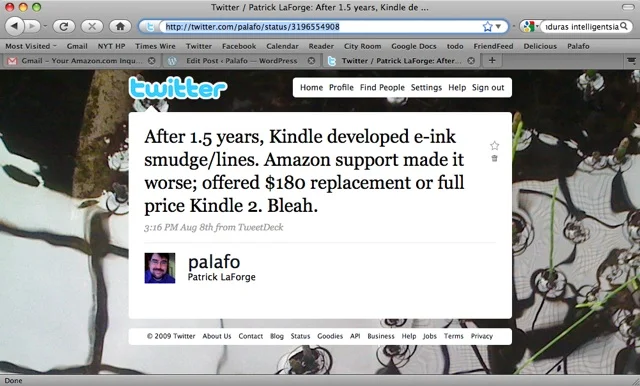

@palafo: Is talking to people a waste of time? Sometimes it is, I guess. Twitter is a conversation. You get what you put into it. I don’t think talking to our readers is ever a waste of time.

That’s the short answer. Here’s the long one.

I view my Twitter account @palafo as part of my identity. It does not belong to The Times any more than my name does.

But The Times is part of my identity, too, because I am an editor here. For that reason, I behave on Twitter as I do in the newsroom or on a public panel. I try not to say anything on Twitter that I wouldn’t say in front of a live microphone with cameras rolling.

Background: I joined Twitter in 2007 when few people in the newsroom knew what Twitter was, and I didn’t hide my Times employment, but I didn’t advertise it at first, either. At the time, I was on the Metro desk, where I was editor of the City Room blog. We were always looking for ways to engage online with New Yorkers. The blog had an automated Twitter feed, but it had fewer followers than my account (still true, alas). It turns out that a personal touch on Twitter was more successful than spitting out headlines. So I identified myself on Twitter as the blog’s editor and started interacting with readers through it.

In my current job, editor for news presentation, I oversee copy editing and production for print and Web, and I continue to experiment with all the social media tools, including Twitter. I have a responsibility to understand the digital media innovations transforming journalism and the news business.

But I admit it: I love this stuff. I’ve been on the Internet since it was the Arpanet, when I was a teenager in the 1970s. Twitter reminds me of the computer bulletin boards, Usenet newsgroups and other online forums of the early days. The rest of the world has finally caught up.

Now, to your specific questions...

The Public Editor:What are the benefits to you of tweeting and what kind of content do you tweet?

I follow about 1,100 news organizations and blogs, competitors, Times colleagues and other journalists, people who follow the news closely, media critics, tech experts, some friends and acquaintances and anyone or anything anything else that catches my interest. I try to pare the list back from time to time. It was easier to follow when it was closer to 500. I also have a number of Twitter lists with even more accounts that I consult from time to time. I have a list that shows how Twitter looks to me.

These Twitter users “curate” the Web for me, which means they find, analyze and comment on useful links that interest me far more quickly than I could ever do for myself. If they link to something that grabs my attention, I will generally look at it or save it for later. I don’t read everything. I dip into Twitter when I have time. The analogy is a cocktail party. You can’t join every conversation, but you drift through the crowd and stop now and then. Important or significant news gets repeated, and it sometimes shows up in the trending topics.

Often I learn about news from Twitter. Your predecessor, Clark Hoyt, wrote about Twitter’s role in a big story in 2009 that was an aha moment for me and the newsroom, when a jetliner landed in the Hudson River.

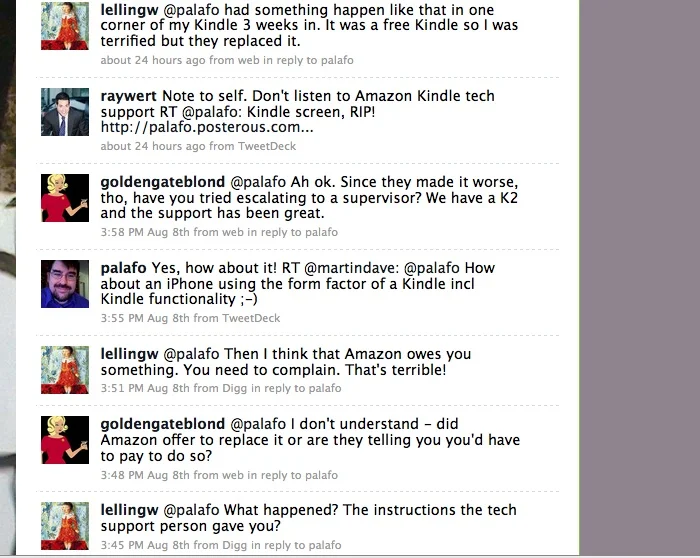

But Twitter is more than a tip sheet or a place to find sources. It is important to remember the “social” part of social media.

Since the people on Twitter share so much useful information with me, I try to give back to them by interacting there. I don’t write about my lunch, or anything too personal. Mostly, I share links. The links are generally to news articles, blog posts, interesting uses of digital media, pictures, video, you name it. I follow our newsroom policies for personal Web writing, which permit journalism reflections, and lively commentary on one’s avocations like music and food, but forbid taking stands on divisive public issues.

I am not a Times spokesman or a marketer. I share a lot of our journalism on Twitter, because it is excellent. I don’t feel obligated to do so, and I don’t share everything. The article has to interest me personally as a reader and be something that I think my Twitter followers will like. People can tell when you are just randomly pumping your own stuff or your employer’s offerings. Luckily, Times journalism — I am biased about this -- is almost always of a high caliber.

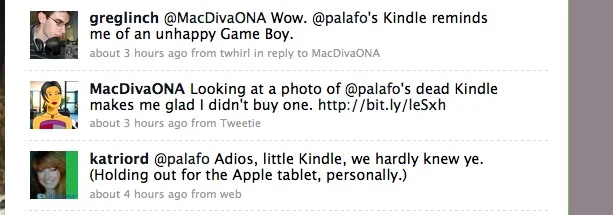

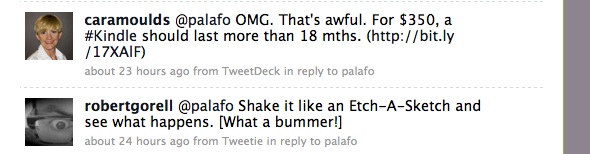

Unlike Facebook, Twitter is asynchronous, so I am followed by about 10 times more people than I follow back. Sometimes they want to talk to me. So I read all “mentions” directed at me on Twitter. People know I’m busy, so they don’t abuse the opportunity. I ignore anonymous gripes, but people who use their real identities are generally polite even if they are upset about something The Times has done. If someone like that has a question, a correction, or a criticism, or a technical problem, I try to answer it or find someone who can.

The Public Editor: Do readers benefit and, if so, how? Does The Times benefit and how?

As everybody knows, over the last several years Twitter and social media have grown at a great rate, and many news sites, including The Times, now receive a growing amount of traffic from referrals on Twitter and other social media sites. Having our journalists on Twitter also translates into credibility with readers who live their lives online. It shows we understand the digital world and how it works.

More important, The Times and its readers benefit from a newsroom that understands digital culture and is familiar with the conversations about the news on Twitter, Facebook, Reddit, Tumblr, blogs and similar sites.

The news report and readers also benefit from the news-gathering power of tools like Twitter. Brian Stelter has used Twitter to develop ideas that have turned into articles.Rob Mackey of The Lede blog (@thelede) has shown how news events from earthquakes to political revolutions have played out on Twitter, YouTube and other social platforms.

In general, sites like Twitter have accelerated news competition. Not all of the effects of high-speed social media have been positive. Rumors and bad information spread faster — but they are also debunked faster. The pressure to compete in real time, and the transparency and immediate feedback from readers can be nerve-racking and destabilizing. But competition is good for everyone. We are closer to our audience, and they are closer to us. That results in a better news report.

The Public Editor: Are there any costs to you, or the Times, of using Twitter as a tool? Surely, it takes time. Does that time subtract from the time available to do your job? Any other costs?

It doesn’t take away from the job. If anything, the job probably eats into many more hours of my personal time than it should. Or so my wife tells me.

Part of my job is to read The Times and its competitors, a task that could fill every hour of my day if I let it. Twitter is a useful tool for figuring out priorities for my attention. It doesn’t take that much time. At work, I use an iPhone app, and there’s always down time, walking down the hall, waiting for stragglers at a meeting, riding the elevator, while I’m grabbing a bite to eat. It only takes an extra second to save a link or share it. At home, I’ll look at Web sites and Twitter on my laptop, phone or iPad while I’m watching TV or listening to music, a podcast or an audiobook. I am busiest on Twitter at night and on weekends. The Web and Twitter have definitely cut into time I used to spend reading books.

Another cost is the occasional irritation of family and friends, although e-mail is a worse cause of inattention and wasted time. I’ve been trying harder lately to turn off devices and get off the grid away from work. It’s not easy. The people I know are like me: They talk about the news a lot, and they want to know the latest news, too.

###

Addendum:As I mentioned on Twitter, I might have chosen a different metaphor had I known the headline was going to be "A Cocktail Party With Readers." The analogy is as old as Twitter, and useful for newbies, but it doesn't capture everything:

Other analogies for Twitter: Cafe. Neighborhood. Village square. Crowded public meeting. Parade ground. War zone.Sun Mar 13 15:41:30 via webPatrick LaForge

palafo

@palafo Classroom back row. Street corner. Water cooler. Kindergarten. TED.Sun Mar 13 15:48:12 via EchofonMiss Scorpio

gemini_scorpio

@palafo Real-time peer-review; collaborative footnotes and bibliography.Sun Mar 13 16:07:31 via webJenny K

jenny_flaneuse

@palafo Roman bath house with hash tags. #TwitterSun Mar 13 15:44:18 via EchofonDavid Herrold

davidherrold

@palafo I thought analogy worked well to convey level of involvement in conversations, but i'd prefer cafe for a.m., maybe mosh pit for p.m.Sun Mar 13 15:55:36 via webSasha Koren

SashaK

@palafo@thepubliceditor How bout lifeline? http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/03/11/the-internet-kept-me-company/Sun Mar 13 17:30:20 via webSandra Barron

sandrajapandra

[See also: Basic Twitter Tips for Journalists.]

One notable aspect of the

One notable aspect of the